The Mother of all Fanzines: 'Millerntor Roar!'

How the threat of their stadium closing inspired St. Pauli punks to publish a magazine — and create an enduring image for their club

Fans. Fußball. Viertel.

I reckon even the least competent German speaker can work out the first two, but I’ll spell it out.

Fans. Football. District.

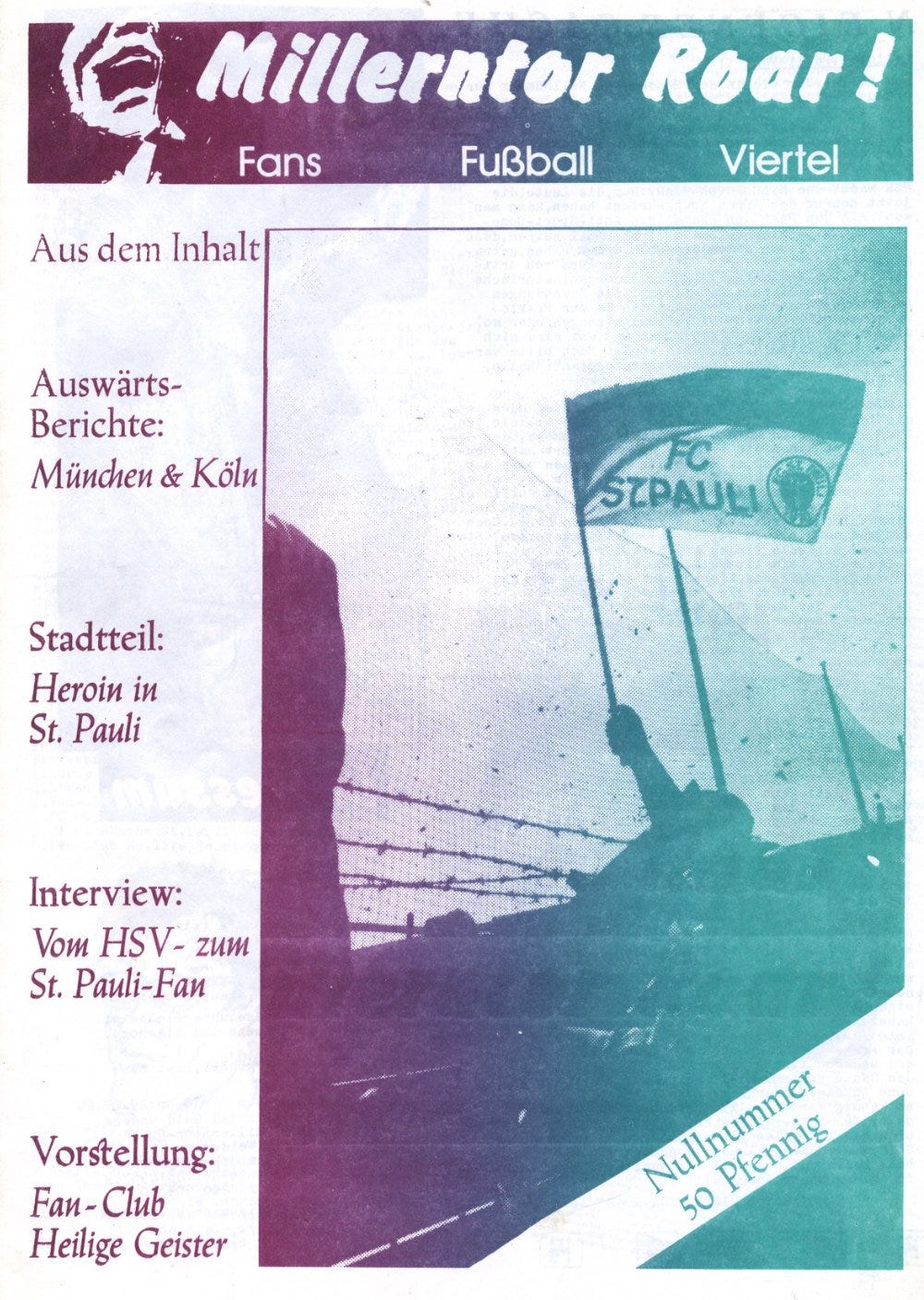

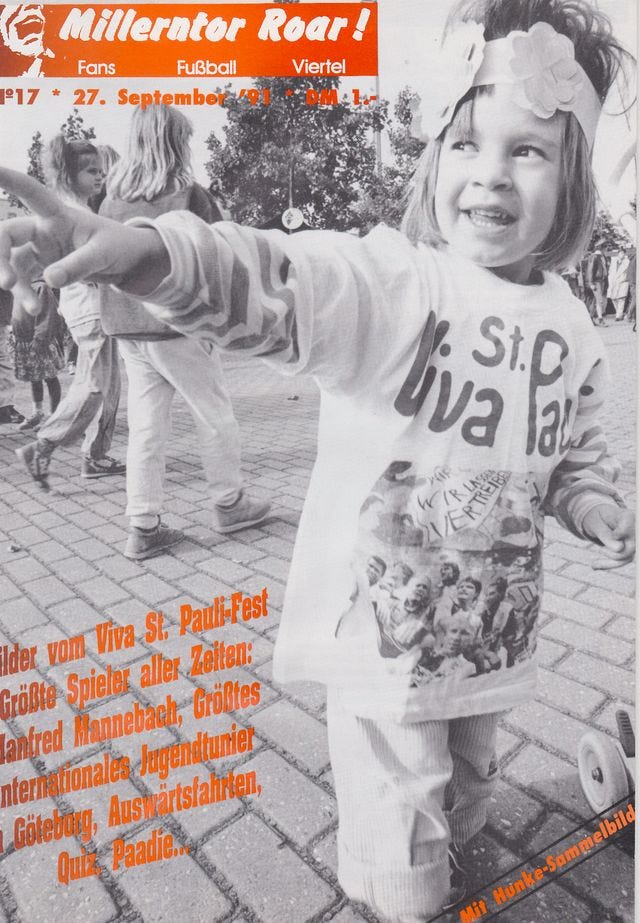

Those were the words adorning the masthead of Millerntor Roar!, a fanzine founded by St. Pauli fans in 1989. Created by a small editorial team of punks the publication has had a profound impact on both the anti-fascist image of the club, and the football fanzine scene in Germany as a whole.

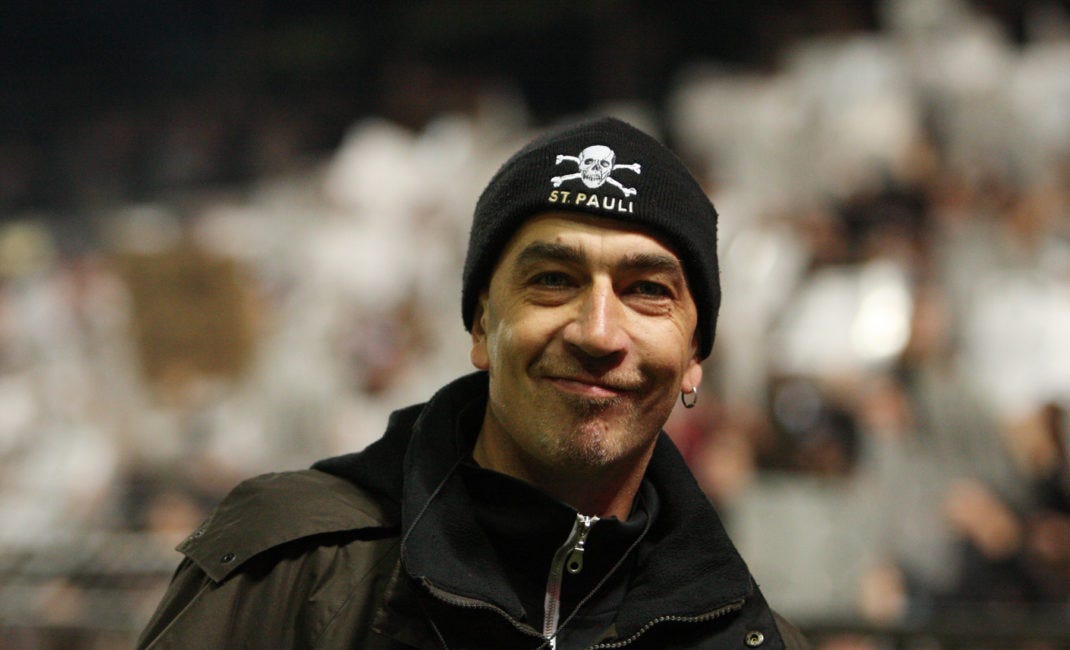

“It was a group of about sixteen or seventeen people,” says Sven Brux, one of the founders of Millerntor Roar!, and a fixture of the St. Pauli scene.

“We’d meet every Thursday and decide what we’d want to write. Every matchday we’d be outside the stadium. It started with around 1,500 copies, but by the end we were printing around 3,500 magazines an issue. We sold it outside the ground, on the terraces, at different pubs, even at some record shops in England.”

In his book St. Pauli: Alles Drin (St. Pauli and Everything in It) the author Christoph Nagel describes Millerntor Roar! as the ‘mother of all fanzines’. Writing in their history of the Bundesliga, Christoph Biermann and Phillip Köstel described the publication in similarly reverent terms:

"Humorously, intelligently, politically and with a large portion of self-irony, the fans reported on their everyday lives as supporters, protested against soulless new stadium construction and the destruction of standing areas, described adventurous away trips and poured their scorn on all the club's attempts to turn supporters into customers."

Brux explains the magazine was born out of a growing movement of fans on the terrace, as disparate groups of St. Pauli supporters unified to combat the closure of the Millerntor Stadium. A consortium of Canadian investors proposed building a new stadium called ‘Sport-Dome’, an all-seater municipal arena which would also house a shopping mall and hotel.

“At this time, The Millerntor was three sides standing, with one seated stand that had rotting wooden benches. It was clear we needed a new stadium,” Brux tells Bundesletter. “We didn’t want one like this, with a congress centre and rubbish like that.”

A coalition of opposition quickly started to form. Led by Brux and his group of punks known as the ‘Black Block’, more moderate fans and inhabitants of the neighbourhood threw their weight behind a protest movement.

“People were afraid of gentrification,” says Brux. “There was a good mix of punks, people from the neighbourhood and just normal fans who didn’t get involved in protest usually.

“We told people, if this happens we will become like Arsenal. This place will be a library. Normal football fans understood that, and they got behind our organisation.”

Tactics included fan marches and leafleting before games. Most famously, in a match against Karlsruhe SC in March 1989, a five minute silence was observed, signalling the type of atmosphere the club could expect if the plans were followed through. Such silences have become common tactics in German fan protests today. Union Berlin fans, for example, have protested the commercial model of RB Leipzig by abstaining from signing for the first fifteen minutes of fixtures between the two clubs.

The demonstrations were successful. Not only did the fans stop the construction of the ‘Sport-Dome’, but they instilled a new culture of anti-commercialisation and left-leaning politics that are the club’s hallmark today.

“Everything that characterises the club today has its origins in this period,” says Thomas Glöy, a historian at St. Pauli’s club museum.

“Until the mid-1980s, St. Pauli was a completely normal and mostly unspectacular club with a very manageable fan scene that did not express itself publicly and had no influence on the club's management. For a long time, the club's top management was still very middle-class and conservative, while the composition of the public had long since changed.

“The fact that political issues are now also explicitly covered in the club's official media and that the majority of the supervisory board are very close to the fans (and the majority are female) is all a result of the participation of the fans, which began in the mid-1980s and was carried into club politics from the spectator stands, especially from the mid-1990s.”

Millerntor Roar! was crucial in maintaining that momentum. Brux says the idea coalesced due to fans feeling underserved by the club’s official media, as well as the DIY aesthetics of punk and a burgeoning fanzine scene in the UK.

“In the spring of 1989 we had a terrible away day in Munich. Some trouble with the police,” he explains.

“The club programme only covered the good stuff. We wrote in and said, ‘you wrote only about good things about the trip, but it wasn't true. We had some bad experiences, and here's the story.’ They refused to print it for whatever reason and we just thought, wow!

“After our successful experience with the protest group we thought, ‘why not give it a go?’ Our own magazine. Some of us had knowledge of the scene from our punk background. We got in touch with the English magazines, people like When Saturday Comes. We liked the humour. We liked the irony.”

From July 1989 to the end of the 1993 season, Brux and his group of friends produced a total of 28 magazines covering the games, the fans and the neighbourhood around the stadium. The first issue, a 16 page magazine in A4, would set you back the princely sum of 50 pfennigs, about €0.25 in today’s money.

“We talked about the games, jokes from the terraces, typical shit for a fanzine,” says Brux wryly. “But we were political too. We wrote stories about local drug dealers, how rent prices were going up.

“The first issue was put together using scissors and glue sticks. By the second copy we were designing it on a computer.”

True to the radical left spirit of his friendship group, articles were initially printed without a byline. The statement instead was attributed to the editorial team as a whole. Brux says this helped the team make bolder statements that would increase pressure on the club to affect change. Was that how they measured their success?

“It was a mix of everything,” says Brux. “We wanted to see sales go up, but we also wanted to see changes in the club.

“For example, at the time concession tickets were given to children, students, military and retirees. What about unemployed people? They have no money either. A retired person can be very wealthy. After we wrote about it, the club made the change.”

Brux cites other examples of pressure from the publication changing the club’s ethos. During the race riots of the 1990s, Millerntor Roar! wrote positively about immigration, organising meetings between groups and pressuring the club to play a symbolic friendly against teams with significant immigrant populations in the city. The Kiezkickers would eventually play against Galatasaray in the summer of 1992.

Read more about the unrest in Germany in the 1990s by checking out our recent trip to Hansa Rostock’s Osteseestadion.

“Everyone was reading it,” says Brux. “The staff, the players, the chairman. Even just normal people in the bank would say ‘Oh, I'm not a punk rocker, and I don’t like all this, but the magazine is very good!’”

That did bring some negative attention. Despite the club’s burgeoning leftist identity, there were pockets of fans that didn’t buy into the magazine’s ethos. Brux describes these groups as “broadly right wing” and “hooligans”, but falls short of describing them as “Nazis”. He refers to a brief skirmish where a number of these fans attacked the ‘Black Block’ during the 1990 World Cup, but any organised right wing movement was quickly drummed out of the club support.

Further issues did come from other fanzine publishers however. Glöy tells me over email that while Millentor Roar! wasn’t the first fan publication in Germany, it was the pioneer in spreading left-wing ideology around the game.

“The magazines that existed until then were more or less clearly on the right politically,” he says.

“In addition, most of the reports were about beating and drinking and were often very sexist.

However, the example set by Millerntor Roar! gradually led to many imitators, and in the mid-1990s in particular there were numerous high-quality fanzines at many clubs, which also networked with each other. The first cross-club fan alliance BAFF (Bündnis aktiver Fußballfans), founded in 1993, also had staff overlaps with the fanzine editorial teams in many locations.”

Brux tells me about these meetings, and while he does refer to like minded fans popping up around the time, the stories are largely negative.

“We were invited to one of those first meetings, it was in the Rhine area. There were 30 or 40 people there, all right wing just waiting to abuse us. Not physically, but with the classic line: ‘You left wing bastards brought politics into football.’ We were waiting for that.

“We gave them all the examples of the fascists bringing politics into the game. The abuse of black players, throwing bananas, the organisation of Nazi groups and their propaganda, the National Front in the UK, all that shit from the 70s and 80s. We said, ‘look, tell us who really brought politics into football?’ And they couldn’t answer that question.”

Steadily, a number of fans began contacting the team, asking for their tips in starting a similar publication to Millerntor Roar! A scene that looked at football differently was starting to grow.

“People would write to us after they found our magazine in a record shop,” says Brux. “That brought a new culture for German football.

“We swapped magazines. They wrote about us, we wrote about them. A new ethos was spreading, and Millerntor Roar! was a big part of that.”

Millerntor Roar! wound up in 1993, a decision that came from a splintering of the editorial team. Unbersteiger, of which Brux was initially a part, reflected a more moderate take and is still running today. Unhaltbar was far more “political and sharper in its writing”, says Glöy. The latter publication published its final issue in 1999.

Brux now works as a safety officer for the club, and has been involved either with the fan group or the club itself for the past thirty years. Eventually, his increasing exposure to the inside machinations of the club meant he couldn’t contribute to fan magazines. Looking back on the role he and his comrades played in the fan movement of the 90s, which gives St. Pauli it’s international reputation today, he’s aware of the impact they’ve had.

“If you look at the club in 2024 and see what we have. Not just the magazine, but the anti-Nazi stickers, the influence supporters have inside the club. Our chairman published a fanzine when he was younger. A lot of people from that time now have jobs in football, and are putting these ideas into practice. If you look back at all that from the last 35 years? It’s something to be proud of.”

Wörterbuch-Ecke — German football phrases you need to know

Sprichwort: Zuckerpass

Direct translation: Sugar pass

Spiritual translation: ‘What a ball’

Five Champions League medals. A World Cup winner. One of the best passers of the ball to ever play the game.

For all his obvious merits, Toni Kroos isn’t universally loved in his homeland. Or at least he wasn’t until this past summer.

After completing 101/102 passes in the opening game of Euro 2024, the veteran midfielder was finally receiving his flowers. Yes, it was a virtuosic display (against a terrible opposition, Germany battered 10-man Scotland 5-1) but there were still crumbs of evidence for his naysayers.

His manager Julien Nagelsmann used the opportunity to put one thing to bed. “He was very, very good,” Nagelsmann said of his performance. “I think 99% of his passes were completed and they weren't only sideways. That nickname is crazy. Crazy.

“Toni is still one of the top three players in the world when it comes to finding team-mates between the lines, creating chances and setting up goals.”

Nagelsmann was referring to Kroos’ moniker ‘Querpass Toni’, the joke being the midfielder only passes the ball from side-to-side (‘quer’ meaning square).

No man can complete 99% of his passes exclusively trying to split open defences with raking diags or surgical through balls, but to claim Kroos isn’t capable of the sublime is simply false.

When Real bested Bayern in a Champions League semi, one of his assists was so good ESPN devoted a whole article to it. His delivery at set pieces has always been exemplary. His retirement is clearly causing headaches for Los Blancos, as they look to balance their new Galacticos without the vision and grace of their midfield maestro.

Whatever caused his lack of popularity, be it his aloof nature or having the temerity to leave Bayern, one thing is indisputable. The man’s right boot is so sugary you could dip it in your tea.