Walking in Berlin: A Football Fan in the Capital

A soggy tour of the Haupstadt’s football history

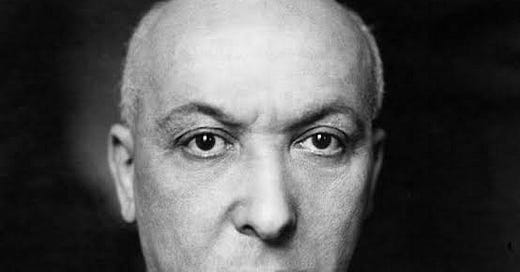

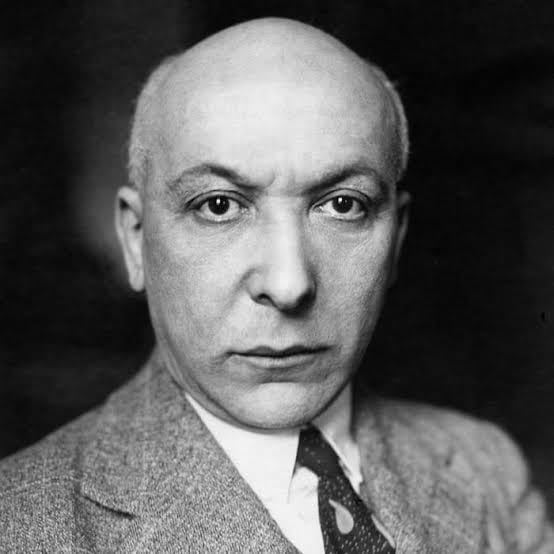

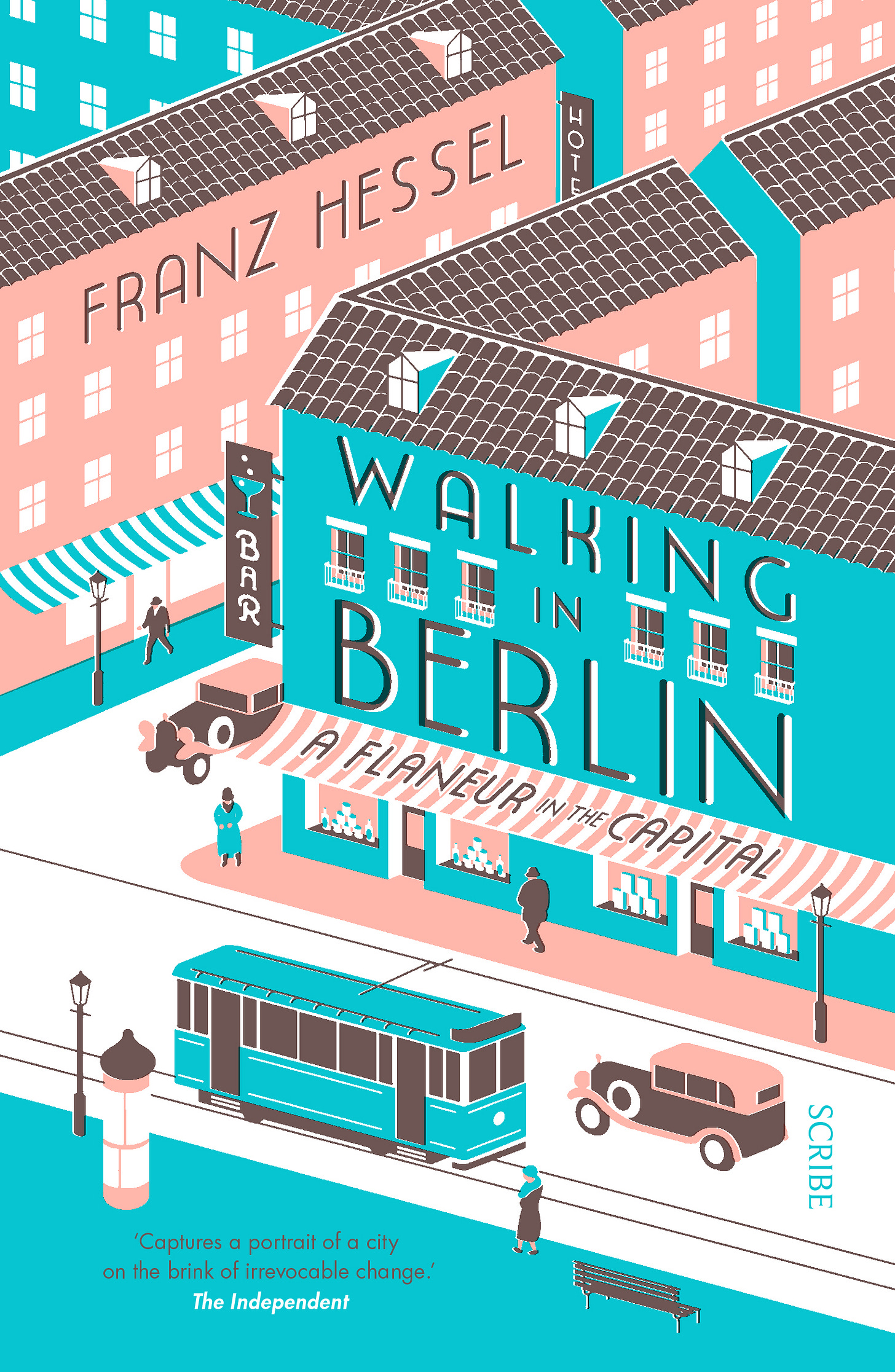

In my attempts to expand my reading on Berlin, and Germany as a whole, I recently picked up a copy of Franz Hessel’s Walking in Berlin: A Flâneur in the Capital.

Hessel’s work is a vivid description of Berlin in 1929 during the Weimar Republic, the interwar period of German democracy that would eventually fall with the ascension of the Nazi Party in 1933. It tells the tale of a city in flux, of migrants and blow-ins attracted by the city’s loose attitudes to taboos. Hessel describes Berlin as ‘a city always on the go, always in the middle of becoming something else’. The more things change, the more they stay the same.

A ‘flâneur’ is a man who saunters around observing society. As a 32-year old man with no driving licence, and the steadfast belief that the entirety of London’s Zone 1 should be pedestrianised, I immediately felt a kinship with Hessel. However, I’m not one for sauntering. I’m more of a marcher.

What does this have to do with football you might ask? Well, inspired by Hessel’s text, I spent my German Unity Day (3rd October) walking Route 1 of the ‘Fußball Route Berlin’, a self-guided cycling tour of landmarks and notable locations in the history of the German game. Considering I would be ambling for a good three hours, and my physio told me to avoid walking long distances because of tendonitis in my knee, it probably wasn’t the best idea. Anything for content.

Regrettably, my journey starts at Brandeburger Tor. Of course, this landmark is synonymous with the Haupstadt, one of its few immediately recognisable structures. Now I’ve lived in Berlin for a few years, there’s little here for me, my interest in overpriced Currywurst and pointing out where Michael Jackson dangled his baby out of a hotel window dimmed.

Today, Pariser Platz is bustling with pro-Ukraine demonstrators. Signs read ‘Kein Appeasement fur Putin’. Across the city, anti-war protests attended by ‘well over 40,000 people’ according to its organiser (police figures estimate numbers in the ‘low five figure range’) call for an immediate cessation of arms deliveries to Ukraine.

A short walk down Unter Den Linden, barriers on the pavement block passage past Russia’s grand embassy. In the almost three years of Russia’s ‘special military operation’ I’ve seen maybe two or three people enter or exit this palatial residence. Today, a security guard looks at me warily as I take a couple of shaky photos for posterity.

Reminders of the fraught state of global politics are everywhere. Turning down Freidrichstraße I happen upon a pro-Israeli women's march. A rainbow patterned Star of David is proudly hoisted behind a banner reading ‘Believe Israeli Women’, and that ‘fighting against all Anti-Semitism’ will lead to ‘universal feminism’.

Considering Hessel’s book is written on the verge of the collapse of the global and German economy, there is little consideration of politics in his work. In the year of publication, there was an outbreak of political violence in the city known as ‘Blutmai’ (Blood May) after the Communist Party of Germany defied a ban on public gatherings by the city’s Police force. Some 33 civilians died in the unrest, with 1,200 arrests made.

Hessel was far more interested in the city’s vices. In the chapter titled ‘Lust For Life’ he writes: “In his zeal for pleasure, the Berliner of yesterday still lapses into the dangers of accumulation, quantity, excess. His coffee houses are establishments of pretentious refinement.”

These words echo in my ear as I step into the modern coffee shop: a Pret-a-Manger. As I reluctantly part with €4 for a lukewarm and half-hearted decaf flat white, a jauntily designed screen behind the counter beams down at me ‘Born in London, Made in Berlin with Love’. Pretentious? Absolutely. Refined? Far from it.

Hessel declared Freidrichstraße was once ‘Berlin’s centre of sin’, as it housed 200 cabaret houses and variety theatres. The painter George Grosz wrote of the street during the 1920s: “Freidrichstraße was crawling with whores”. This writer declares the street ‘Berlin’s centre of Boredom’. For a city largely untouched by commercial chains, it houses a Starbucks, the aforementioned Pret, McDonald’s and KFC. There are big businesses, mediocre eateries and souvenir shops selling ‘verified’ fragments of the Berlin Wall.

Where there are tourists, there is of course a flattening of variety. But also, where there are tourists, there’s something of immense public interest. Freidrichstraße is as significant a road in recent modern history as any. Here stands Checkpoint Charlie, a crossing point of East and West during the partition of Berlin in the Cold War, a symbol of the decades long standoff between the US, its allies, and the USSR and its vassals.

It’s also where I make my first two stops. At Friedrichstraße 71, the first attempts at regulating German sport were made. Here Georg Demmler and Fritz Boxhammer founded the Deutsche Sportbehörde für Athletik (German Sports Association) in 1897. This organisation would in turn spawn the DFB, the association that still governs football in Germany today. Around the corner on Mauerstraße, the first edition of Kicker Magazine was published in 1920.

As I cross from East to West past Checkpoint Charlie, a steady rain begins to fall. Some day trippers scatter to the nearest cover, while hardy souls desperate for that perfect Instagram pic pull their raincoats over their head. I set a quicker pace, slightly concerned I’ve made a terrible decision. Who’d give up their day off to walk in the pouring rain?

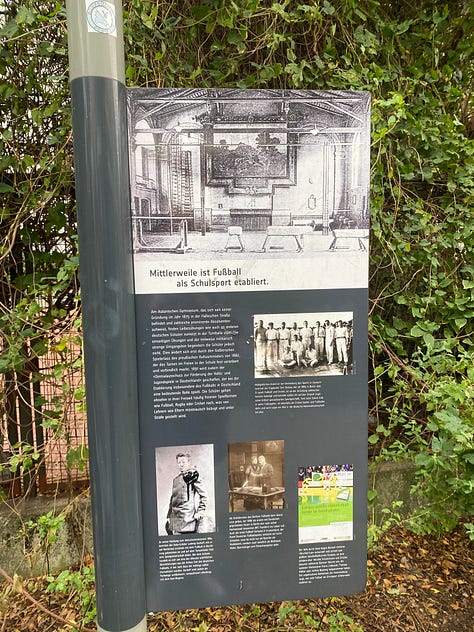

That doubt grows as I reach my next stop. Where Hessel describes a beautiful city recently marked by the influences of the Bauhaus movement, I happen upon a symbol of the apathy of modern existence. A fly-tipped flatpack sofa. Next to the rubbish, I learned of the Askanisches Gymnasium, a prestigious school which boasts notable alumni in the fields of politics, science and sport. Prior to 1882, all physical education took a military style of ‘monotonous exercise’ with a ‘harsh-tone of instruction’. A decree by Prussia’s Minister of Education mandated children must partake in outside physical exercise, allowing ball games such as cricket, rugby and football to gain popularity. A student of Askaniches Gymnasium, Ludwig Aschoff, is credited with writing one of the first accounts of football being played in Germany. His 1884 essay details his peers playing an unorganised match on the Templhofer Feld.

After shielding from the rain in an alcove for a few minutes, I set off on the longest walk of the journey, crossing the canals of Kreuzberg and turning towards Viktoria Park.

Kreuzberg, like most of inner Berlin, is a place of constant contrast. Where one kiez is brimming with activity and people, the next block can feel like a ghost town. The rain and shuttered shops for the bank holiday doesn’t help with the feeling I’m the only person who's mad enough to be out in this miserable weather.

The district has historically been a centre of immigration, and is notable for its sizable Turkish population. It hosts many of the city’s diaspora clubs, including Hilalspor, Türkspor and Türkiyemspor, a club that but for an eligibility snafu would have reached the 2.Bundesliga in the early 1990s.

Their home ground is my next stop. The stadium now known as Willy-Kressmann-Stadion (named after the post-war mayor of the Kreuzberg district), was first built on Katzbachstraße in 1914. In 1924, an expansion designed by Georg Demmler expanded the capacity of the stadium to 12,000 seats. Prior to the founding of the Bundesliga, local football leagues and competitions were well attended, and many of the clubs in Kreuzberg hosted large attendances at the Willy-Kressmann-Stadion over the years. In 1954, a game between BFC Südring and Hertha BSC drew a crowd of 10,000 people.

Thankfully, the rain abates as I cut through Viktoria Park. It’s here where I felt like a true flâneur, allowing myself to take the scenic route. The park is centred around the hill ‘Kreuzberg’, the highest natural point in the city and the source of the district’s name. Sitting atop the 66m ‘peak’ is a memorial, built by King Freidrich Wilhelm III in 1821 to celebrate the liberation of Europe from Napoleon Bonaparte. Rather than traipse up the slope, I decide to walk the path along the waterfall that cascades down from the monument. Hessel himself stood at the bottom of the hill, although his attention wandered more towards a woman plastering a billboard than the pleasing sounds of the stream.

A short walk along Kreuzbergstraße, in an unassuming apartment building, a 17-year-old student founded the oldest German football club still active today. BFC Germania 1888 was founded by Paul Jastram, his brothers and friends, and was a founding member of Germany's first football league ‘The Bund Deutscher Fußballspieler’ (BDF). That league would quickly dissolve due to disagreements over the eligibility of foreign players. With Germania’s founders arguing against migrant players, they were denied access to the newly formed Deutschen Fußball und Cricket Bund (German Football and Cricket Federation).

I cross Mehringdamm into Bergmannkeiz, an affluent neighbourhood largely untouched by the bombing of the Second World War. The stuccoed 19th Century architecture, dingy but well stocked record shops and a fine selection of cafes, bars and restaurants makes this a regular haunt of mine. As I walk down Bergmannstraße I come across the latest stop on the tour. Here in a cellar bar, the first meeting of the Verband Deutscher Fußball Spielvereine (the association of German Ball Sports Clubs, now known as the BFV, or Berlin Football Association) was held. This organisation became a leading force in the expansion of the German game, standardising and codifying rules for associated clubs.

Somewhat weary, I turned my compass south towards Templhofer Feld. The Feld is a foundational part of the Berlin experience, a wide open expanse that has been used as a parade ground and an airport for both military and civilian air travel. For modern Berliners, it’s a space for grilling, cycling, gardening, and meeting with friends, as well as a home for refugees before they’re assigned more secure accommodation. The first records of games between football clubs in Berlin take place on the feld. In a short chapter on Tempelhof, it is here that Hessel makes his sole mention of football, andnods to Germany’s military history that would soon again become its future:

“Athletic fields start where the airport ends, and the boys run over to their soccer teammates. This large territory belongs to the children and the aeroplanes. And yet it wasn’t so long ago that it was the site of the old-fashioned parades and military reviews. The very opposite of athletic elasticity prevailed here: the rigid goose-step of the guard.”

As I looked across the vast expanse of the feld, slightly soggy, with a pulsing pain in my injured knee, I really started to question whether I’d lost my mind. I decided to incentivise myself in the only way I really knew how: I’d buy myself a beer at the end of the journey.

With more vim in my step, I crossed Columbiadamm, and set across Hasenheide. As Hessel taught me, that directly translates as ‘Rabbit Heath’, but as he glibly puts it, “there aren’t rabbits here anymore, and there’s no heath either”. The park forms a natural border between Kreuzberg and Neuköln. Unsurprisingly, considering the Turkish influence in both districts, it’s the site of the first Muslim burial place in Berlin.

It’s most famous for housing the first Turnplatz, or open-air gymnasium. Here in 1811, Freidrich Ludwig Jahn, constructed wooden exercise structures that would become foundational elements of German exercise. A statue of ‘Turnvater Jahn’ (Father of Gymnastics Jahn) commemorates his contribution to gymnastics, and general sports administration; a municipal stadium used for soccer, American football and athletics in Prenzlauer Berg is also named after the teacher. While he was widely celebrated in his own time, Jahn’s writing is now widely criticised as anti-Semitic and overtly nationalist, with notable critics of the Nazi ideology such as Peter Viereck claiming he was a spiritual founder of the party.

I’m sure the ‘Turnvater’ would be a fan of Hermannplatz. Busy, loud, and unflinchingly multicultural. Today, it’s sparsely populated, the noise instead coming from a procession of cars tooting their horns in celebration of a wedding. A few blocks on, I reach my final destination. The bar. Drying off with a pale ale in hand, I feel I’ve done the spirit of the flâneur proud.

Wörterbuch-Ecke — German football phrases you need to know

Sprichwort: Bombenschuss!

Direct translation: Bombshot

Spiritual translation: Screamer

About eight years ago, I had one of the best days off work.

Recovering from a weekend of partying in Manchester, my housemate and I parked our arses on the sofa, and spent a whole Monday watching Premiership Years. A foundational moment in our friendship, we still regularly cite that day when talking about our mutual admiration for the pioneers of the ‘best league in the world’ (please read in ironic air quotes).

There’s Les Ferdinand, stealing a yard at the back post. “He always buys a ticket.” Sheer reverence when discussing Peter Beardsley’s first touch, but complete disrespect when talking about his looks. Vinnie Jones, Razor Ruddock, Julian Dicks. Proper football by proper football men.

When we talk about Tony Yeboah, there are only noises. Guttural utterances. Unintelligible growls that border on the erotic. Words cannot describe the majesty of watching the Ghanaian striker thrash a patented ‘thunderbastard’ off the underside of the bar.

Many fans in England may not know the immense cultural significance Yeboah holds in Germany. When he first arrived in Frankfurt as Eintracht’s first black player in 1990 he was roundly booed and abused.

By the time he left for Leeds, he was the first African to take the captain’s armband in the Bundesliga, he’d led the league’s scoring charts twice, and he’d carved a unique place in the history of German football. In the words of Jürgen Klopp:

“Yeboah was one of the greatest strikers who played in Germany apart from Gerd Müller. He had a big impact on society”