Fußball 101: 50+1 Rule explained

The eternal debate: does mandated fan power stymie growth, or protect clubs from the vagaries of billionaires and petrostates?

In this ongoing series, I’ll be looking at some of the unique quirks of following German football. This could be about matchday experience, cultural norms or in this case, the laws by which the game is governed.

Speaking at a press conference in Miami earlier this summer, Bayern’s chief exec Karl-Heinz Rummenigge made his latest appeal to reform football governance in Germany.

For such a canny operator his statement that, “our behaviour in this matter is the cause of condescending smiles in the United States,” seemed a tactical mis-step. In the land of franchises, where teams are routinely shopped around to more affluent cities, stadiums are built using public funds and ticket prices are soaring, it’s doubtful that German fans give two ‘scheisses’ about the opinions of the ultra-capitalist owners and executives in North America.

“Everyone is worried and fearful that we will lose competitiveness if we open up the market,” he continued. “The opposite is true, Germany would benefit from it. Either we go down this path as well or we will wind up paying a price for not doing so.

"We have to stop promoting populism in this republic, which we are pushing to an absurd level in almost all Bundesliga clubs but especially in associations. Germany is not a desert island."

Here lies the crux of the debate around the much discussed ‘50+1 rule’. Does fan power present a negative proposition for the financiers that could improve competition both domestically, and for German clubs in European competition? To invoke populism in this debate is likely a play by Rumenigge to appeal to the risk-averse nature of the German public, which has sought consensus in its politics since the formation of the modern Federal Republic.

There is already consensus on this matter. The majority of clubs and their constituent members support the 50+1 rule completely, and view it as an important line of defence in protecting the culture they hold dear. Where Premier League teams have become the playthings of venture capitalists and petrostates, most professional teams in Germany remain in the hands of their local communities, and most fans wouldn’t consider it parochial or protectionist to keep it that way.

How does the ‘50+1’ rule actually work?

The rule requires a club’s membership to own 50% of the total voting shares in the running of the club, plus one extra vote. This allows the club’s members to maintain control over the club’s direction.

According to the DFL’s rules, any club wishing to play in the Bundesliga or the Bundesliga 2 cannot obtain a licence to compete if they are controlled by an outside investor.

Fans can exercise by taking part in their club’s annual AGM. Here, individual members can make motions and speeches to be heard and voted on by the wider fanbase. Generally long and laborious affairs, sometimes they can descend into chaos.

In 2021, Bayern’s annual meeting made headlines when several members’ speeches on their disapproval of the club’s sponsorship deal with Qatar Airways were cut for time. The speakers in question simply stood on their chair and delivered their opinion anyway, while club executives were jeered and booed from the stage.

Are there exceptions to the 50+1 rule?

There are a few notable exceptions to the rule. If an investor or company can prove upwards of 20 years of support for football in the area of the club, they can take the majority voting rights. Notable and historical examples include Bayer Leverkusen and VfL Wolfsburg. Leverkusen was founded in 1904 by the workers of pharmaceutical giant Bayer, while the city of Wolfsburg was founded in 1938 to house the workers manufacturing the Volkswagen Beetle; the football club that would become VfL Wolfsburg played its first game a few years later.

More recently, TSG Hoffenheim have become the beneficiary of Dietmar Hopp’s investment. Since the SAP founder took an interest in the club from his local village (Hoffenheim has a population of just 3,000) he has invested upwards of €350m. Under his guidance Hoffenheim scaled the leagues, going from the fifth tier to the Bundesliga in just eight years.

After Hopp was granted majority control of the club in 2015, numerous protests against the entrepreneur and the club broke out. Most notably, Borussia Dortmund fans were given a two year ban from visiting Hoffenheim’s stadium for chants and banners threatening physical harm to the tech billionaire. Last year, Hopp announced his intention to return the club to be majority owned by its 11,000 members.

When, and why, was the 50+1 rule implemented?

Historically, German football clubs were wholly member-owned associations. If you look at the full name of most clubs, you’ll see the letters ‘e.V’ at the end. This stands for ‘eingetragener Verein’, which directly translates as ‘registered association’. This can apply to any number of member organisations which are common across Germany.

Following a boom of popularity in the 1990s, the Bundesliga wanted to encourage investment into the game without losing the grassroots feel of their institutions. Most clubs became ‘Gesellschaft mit beschränkter Haftung’ or 'GmbHs', in essence a limited company.

For the majority of Germany’s professional football clubs, this creates a parent company that runs the day-to-day operations alongside the sporting endeavours. As such, fans generally do not have a say in the hiring and firing of directors, coaches or support staff, but instead control the overall direction of the club.

Case studies

Let’s start with FC Bayern München, the most successful club in Germany’s history, and according to the rules’ critics, the biggest benefactors of 50+1.

Bayern are 75% owned by its 300,000+ members. The remaining 25% is split between Audi, Allianz and Adidas. Rather than a GmBH, Bayern are incorporated as an Aktiengesellschaft, meaning stakes in the club are held as privately held stocks.

At Bayern’s Die Klassiker rivals Borussia Dortmund, things are a little more complicated. BVB became the first German club to float on the stock exchange. According to the Bundesliga website, the club’s membership own around 5% of Borussia Dortmund GmbH & Co. KGaA, with around 75% of the shares owned by private investors. However, the management of the club is overseen by Borussia Dortmund Geschäftsführungs-GmbH, which is wholly owned by the club’s members, and thus passes the DFL’s definition of fan control.

Of course it wouldn’t be a 50+1 article without the obligatory dig at RB Leipzig. Austrian energy drink manufacturer Red Bull had been looking for a way into the German market for years, and had actually made attempts to purchase the historic clubs of Lok Leipzig and Chemie Leipzig. In 2009, they instead bought the rights to incorporation from fifth-tier team SSV Markranstädt.

All 17 of the original members of ‘Rasenballsport Leipzig’, were either current or former employees of Red Bull. While membership is technically available for newcomers, the process and costs of joining are designed to be prohibitive. The club remain deeply unpopular with the majority of the German fans.

A number of clubs in the top two tiers are wholly member owned. For example, FC Köln’s 111,000 members retain complete control of the club, as do Union Berlin’s growing membership of close to 60,000 fans.

Who are biggest critics of 50+1, and what are their criticisms?

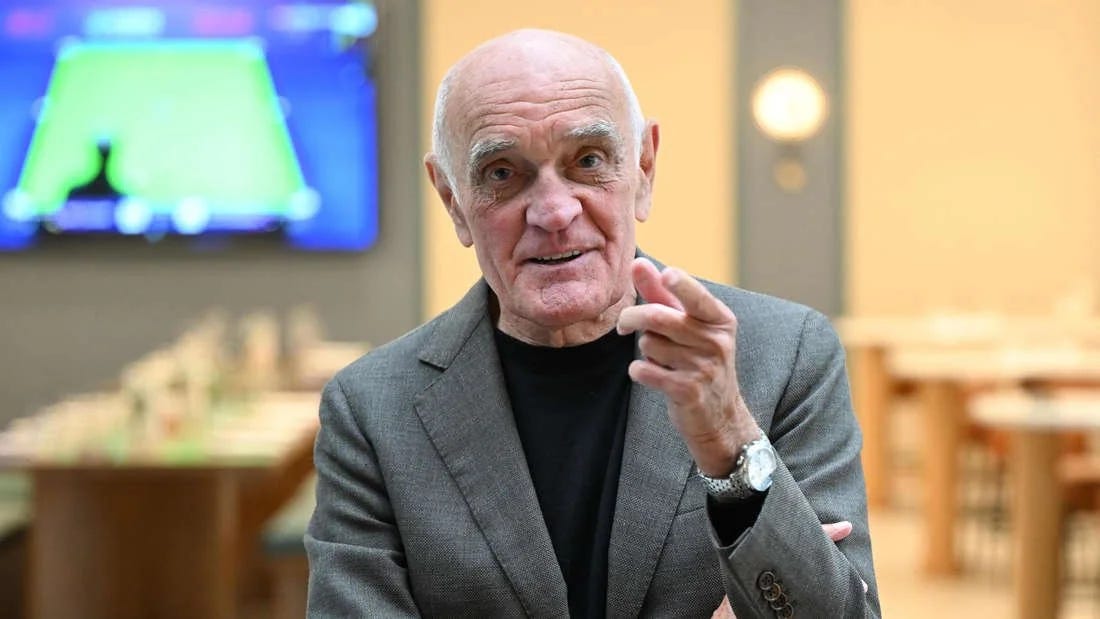

While Hopp has long been the recipient of ire from fans, no man has been a bigger critic of 50+1 than Martin Kind.

In his role as president of Hannover 96, Kind consistently attempted to wrest control of the club from the members, and regularly sounded off about the Bundesliga’s ability to compete against the Premier League.

Following two decades of investment in the club, Kind sought to gain total power in 2018, after he felt he’d demonstrated the required commitment to the club. Fans vehemently protested the development, and voted for Kind’s removal as president in their 2019 AGM. In 2024, he finally stepped down as the CEO of Hannover 96 GmBH.

Since Kind has stepped back from the limelight, Rummenigge has taken up the mantle, consistently highlighting the lack of interest in the Bundesliga from foreign investors. He argues this negatively impacts the wider game in the country, and reduces the Bundesliga’s competitiveness on the European stage. Considering both Bayern and Dortmund made the semi-finals of last year’s Champions League, while Leverkusen and Frankfurt have made Europa League finals in recent memory, this argument is questionable.

There are growing concerns that Bayern’s massive fanbase, (the next biggest membership in the country is Dortmund’s; around 170,000 members) the efficiency with which the club is run under the rule, and its ability to attract lucrative sponsorship deals compared to other German clubs has solidified their dominance.

A fan’s view on 50+1

Allan runs the Hannover 96 UK fan club. Originally from Leeds, and now residing in Berlin, he shares his thoughts on the battle against Kind, and how 50+1 shapes fan culture at his club…

How did you feel about Martin Kind’s attempts to take full control of Hannover 96?

I can't speak on behalf of the entire fanbase, and wouldn't want to as there are far more knowledgeable and lifelong fans of the club, but not great, to put it mildly.

A lot of it seemed to be driven by Kind’s ego. It was about his desire to be in control of everything whilst, bar a couple of years under Mirko Slomka, a culture of mediocrity enveloped the club, especially in the five years since the last relegation.

It’s a soap opera that overshadows everything else, whilst going against the very essence of German football culture.

I don't doubt Kind's money has helped the club at times in the last two decades, but it seems less about his love for Hannover and more about his ambitions and wish to almost beat his opponents.

It completely ignores the consequences of what happens once he is no longer here (it's not controversial to point out he is not a young man). Football clubs belong to their communities, and to the fans, not individuals or companies.

Do you see any reason for 50+1 to be reformed, or even abolished?

Abolished, never. I'm a Leeds fan from birth, I have seen first hand what terrible owners do to your club, repeatedly. I wouldn't want anything like the Premier League in Germany.

Reformed, possibly. I’d like to make it even harder to get an exemption and to see it be implemented properly, because the very fact a fizzy drink team in Leipzig exists, shows it hasn't been applied correctly.

What impact has 50+1 had for the fan culture at your club, and across the country?

It’s had a massive impact at Hannover, specifically Kind's attempts to bypass it. For as long as I've been going (10+ years) the Ultras and Kind have been at each other. KMW (Kind muss Weg — in English ‘Kind must Go’) is ubiquitous at any game, and for a couple of seasons there were complete boycotts by the ultras, leading to dreadful atmospheres, including the first season back in the Bundesliga in 17/18 when there should have been so much positive energy.

As for the whole of Germany, I've no doubt it positively impacts the fan culture. We've seen from protests over ticket pricing and certain club’s investments, to the abolition of Monday night games, that fans here hold sway. It’s because they are both organised, and have a say on how their clubs are run. It's a wonderful thing for the German game.

Wörterbuch-Ecke — German football phrases you need to know

Sprichwort: Joker

Direct translation: A sub that comes on and scores

Spiritual translation: ‘Super-sub’

On a warm summer’s evening, in a game bound for nowhere, Christian Streich is about to take a gamble.

It’s Freiburg’s last home game of the season. A win for the Breisgau-Brasilianer guarantees Europa League football for the first time in over two decades, and keeps the dream of the Champions League alive. As the second-half kicks off, it’s still 0-0, with neither Freiburg or visitors Wolfsburg showing much intent.

On 70 minutes, Freiburg’s manager makes his move. The board goes up, and so too does a massive roar. Here comes club captain Christian Günter alongside Nils Petersen, a rangy if unspectacular centre forward playing his last game in front of an adoring public. He will retire come season’s end.

Petersen is Freiburg’s all-time top scorer, a record he pinched from World Cup winning coach and renowned bogey eater Joachim Low. The East German native landed in the south west almost a decade earlier, finally a prolonged stop after a nomadic existence across the breadth of Germany’s lands and the depths of its football pyramid.

Before this game, 33 of Petersen’s 89 Bundelisga goals were scored off the bench. In the search for a niche to prolong a career that could have easily fizzled out, Petersen became the archetypal ‘joker’, an agent of chaos in the dying embers with an insatiable knack for scoring important goals.

Funnily enough, it’s Günter that makes the immediate impact. Just seconds after coming on, his deflected effort finds the top corner.

A few minutes later, a tame cross slides across the Wolfsburg penalty area. Petersen’s teammate Vincenzo Grifo makes a darting run across the face of a defender, allowing the ball to reach The Joker’s feet. Ever the poacher, Petersen tucks the ball away with minimal fuss. It’s his first goal in the league this season, and it couldn’t have come at a better time. Even though VAR chalks off a second goal, his spirits can’t be dampened. He walks away with an extended-record of 34 ‘Jokertors’ in the Bundesliga, content the dealin’s done.

"After the second goal, I thought I'd get a fresh contract offer…. Sometimes you should quit when you're ahead."

Thanks for reading. If you like my work, but don’t want to a paid subscription, you can buy me a coffee on the link below. See you next week.