Jacob Sweetman is a writer, a drummer, and a keen observer of football in the Haupstadt.

Now the lead for FC Union Berlin's english communications, Jacob has been writing about fußball and Berlin for almost two decades, since moving to the city in 2007.

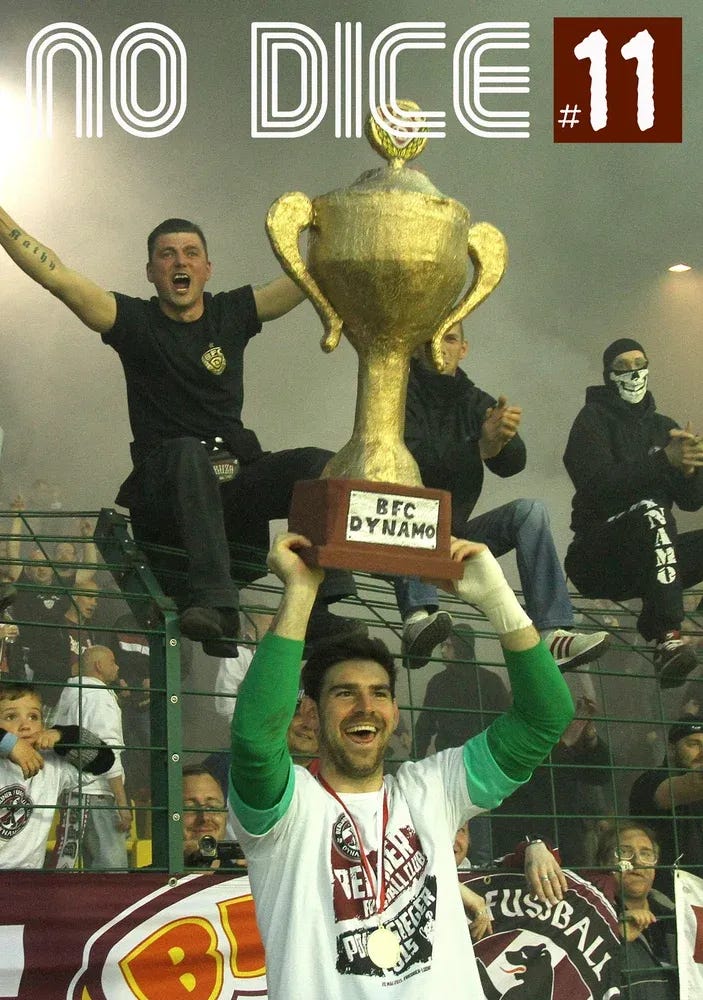

In the 2010s, he edited and published No Dice Magazine, a fanzine that covered the many football clubs in Berlin. In his role with Union, he manages the club's english Twitter feed, writes match reports, and produces video interviews with key figures at the Alte Försterei.

You can listen to the podcast in full above. Or read on for some excerpts from our conversation.

The Bundesletter Podcast is also available on Spotify, and most other major podcast platforms. Subscribe, leave a rating, and share with your friends.We’ll be on Apple sooner rather than later.

Tom: What brought you to Berlin?

Jacob: Chance, really.

I'd spent my life playing the drums, working in record shops, and I was kind of floating around. Didn't really know what I was doing. My wife's an artist and we were living in Brighton at the time. An old friend of mine gave me a call, basically, and said, ‘I've got a job working in in Berlin, if you want it.’

I was working at a place called the Kunsthaus Tacheles, which is this legendary old former squatted art house in on Oranienburger Tor, it was a lunatic asylum basically. I loved it, and my wife loved it. I felt immediately at home in the city.

Tom: You edited No Dice Magazine for a number of years. What kind of publication was that, and what did stories did you cover?

Jacob: It came out of a chance meeting. There were three of us. Ian Stenhouse, our photographer and designer. Stephen Glennon was a writer. So an Englishman, Irishman and a Scotsman, start a football magazine. Write your own punchlines.

The idea was largely Ian’s, it was to hark back to the old fanzine culture that came out of punk and came to fruition with When Saturday Comes.

Our take was to write on football in Berlin. I always used football to write about the city at large really. We wanted to write about the smaller clubs, to write the stories that weren’t really being told, even in German.

Tom: Berlin’s not thought of as a football city. Is that down to lack of success on the domestic scene, and a lack of profile in Europe?

Jacob: I think so. The thing about Berlin is, there’s so much other stuff going on. So many of these clubs are community endeavours, it’s never been about achieving great success. It’s a football city in that there are so many people here who play football, who are involved in football. That tends to get overlooked with the modern focus on success.

Tom: Clubs here tend to have very strong identities built around them. You have Tennis Borussia who are more progressive, BFC Dynamo have their history with the Stasi, there are numerous migrant teams. Is that a sign of multiculturalism or stratification?

Jacob: It’s probably a bit of both. The thing about Berlin is, it’s always been a city that changes very quickly. It’s always been a migrant city. It’s always been on a political edge.

That’s the thing about football, it represents, or it gives a means of representing, these ideals. People will attach themselves to clubs according to where they’re from, where they live, according to their political thought processes. That happens a bit more in Berlin, because this city has kind of been a microcosm for European politics. Go back 40 years, this city was the centre of the Cold War. These things bubble together in a place like Berlin, but it’s present everywhere really.

Tom: People’s idea of Berlin is entrenched in the idea of East vs West. But during the Cold War, people might be surprised to hear of the friendly relationship between Union and Hertha. How has the relationship changed over the years?

Jacob: The change came when they started playing each other. It’s difficult to build up a ‘football hatred’ when you’re literally never facing off.

In 1987 this beautiful documentary called Und Freitags in die Grüne Hölle (And Fridays at the Green Hell) follows a Union fan club from this grotty boozer in Prenzlauer Berg. They go to a game on the last day of the East German Oberliga season, for a legendary away trip to Karl-Marx-Stadt (Chemnitz). We needed a win stay in the league, and we do so with a last minute Mario Maek goal. It’s still one of the most legendary moments in Union’s history.

All the Union fans have got Hertha patches on their jackets. There was this idea of being friends behind barbed wire. There was this feeling that when we play, it would mean The Berlin Wall had come down, and that would benefit everyone in the city.

There was a friendly that eventually happened in 1990, after the wall fell. About 70,000 people came down to the Olympic Stadium.

Of course the relationship changed. When you play each other, you build up these enemies, for want of a better word, just because of the nature of the game. You remember the times they beat you, and you beat them. You gloat to your mate at work, and they take the piss out of you.

Tom: During the DDR, Union’s main rivalry was with BFC Dynamo. They were essentially the team of the state, or at least the Stasi. That animosity is where the idea of Union as a dissident club comes from, how true is that idea?

Jacob: I think it’s impossible for Union to be a true dissident club really .

The idea the East German authorities would allow a truly anti-regime club to exist in its capital is impossible. There’s a phrase, ‘not all Unioner were dissidents, but all dissidents were Unioner’.

We were certainly a club for the outsiders. You’d get the artists, the long hairs, the people in their denim jackets with the straggly moustaches. I think partly that’s because Union never won anything (BFC won ten straight Oberliga titles from 1978-88), and we were outside of the city. That attracts a different sort of crowd. These things always have a kernel of truth, but more often that not its overblown.

Tom: What did you find the first time you came to the Alte Försterei more than 15 years ago?

Jacob: I think I felt welcomed, actually. I’d been a part of this scene, and I’d made a great many friends. They were artists, they were musicians, they were scattered from all corner of the earth, but they weren’t necessarily what I call real Berliners. They were transplants, and we lived in this bubble that wasn’t connected to the real city.

What I found here was real Berliners, who welcomed me unquestioningly because all I wanted to do was go to the football on a Saturday afternoon, and forget all the other bullshit. That was what I was doing.

Of course there are those cliches, you could drink beer and smoke fags on the terrace, and there was a romance about it all. The stadium was falling apart, and only 7,000 people were coming along, but I felt this welcome. I met a guy who I still see now and again,. I spoke no German, and he spoke no English, but he bought me a beer and did his best to explain the club to me.

Outside of the stadium you could be anyone else. Once the ball rolls and you’re in the stadium, you’re one of us, and you’re welcome. That’s what stayed with me.

Share this post